“How are you doing?”

This question has puzzled me recently. Surely you’re not the only one who feels compelled to ask, given the circumstances. After all, these really are unprecedented times and to ask how you are doing is to express compassion – a sort of litmus test on whether you are a decent human being.

Even during more normal times, to ask how you are doing is slightly different from “how’s it going?” or “what’s up?” The former is concerned with a more tangible subject, “you.”

I’m not interested in asking what you are doing, because everyone knows that: looking for cigarettes, busting “Zoomba” classes and watching Tiger King. I’m sure all that has a lot to do with how you are doing. But we’ll get to that later.

So as you try to figure out the answer, I suppose I should start by telling you how I am doing. Whatever that means.

Some housekeeping

A new home! On Substack! It’s great to see you here.

If you’re new, welcome to Cultural Learnings.

If you’re amiss with what you’ve signed up for, I updated this page so you can read more about what to look forward to here and why I’m doing this.

It was a pleasure to hear from some of you on how this newsletter has been of use recently. So, my inbox is open — let me know what you think so far.

Working hard or hardly working

While many are taking it easy, I find myself busier than ever.

I don’t mean to brag. Some people, like Aisha Ahmad, an assistant professor from the University of Toronto, hate that. She says diving into a productive fervour is a sign of “denial and delusion.” “The emotionally and spiritually sane response is to prepare to be forever changed,” she suggests. “We must abandon the performative and embrace the authentic.”

Prior to the outbreak, another epidemic – the one of busyness – was already widespread, dubbing millennials as the “burnout generation.” So, securing our well-being, as Ahmad points out, is totally reasonable.

But to say that people choosing to be productive are delusional is not fair. Ryan Avent of 1843 puts forward a slightly better take on how work can be a positive coping mechanism:

“It is a cognitive and emotional relief to immerse oneself in something all-consuming while other difficulties float by. The complexities of intellectual puzzles are nothing to those of emotional ones. Work is a wonderful refuge.”

I can relate to this. Writing connects me to important questions that give my life value. I live for moments when I can sit back after a long day, admiring a new piece of work.

Yet, I also know this intellectual relief is not true for all jobs and keeping busy provides a false reassurance. Tim Kreider of The New York Times illustrates the other side to this compulsion — one that stems from an inherent precarity. He describes my feelings perfectly:

“I am not busy. I am the laziest ambitious person I know. Like most writers, I feel like a reprobate who does not deserve to live on any day that I do not write, but I also feel that four or five hours is enough to earn my stay on the planet for one more day.”

I’m distracted

Nobody said I was working effectively.

My brain is a Chrome browser full of unread tabs. I have a backlog of messages from 20 different people, all asking how I am doing. I recently moved to a new apartment (yes, during quarantine) without broadband internet – only a spotty mobile hot spot. I find brief moments of respite when I occasionally gain one more bar of signal. This leads me into a pit of dread as I wait for the webpage to load, staring nervously at the spinning circle chasing its own tail.

To be outside the range of internet connectivity does not make it easy to wean off it, especially now as I rely on it to keep in touch with what’s going on.

Paul Lewis investigates for The Guardian why young engineers of addictive technologies, like the red notification, “pull-to-refresh” or the ubiquitous “like,” are concerned with the long-term effects of their inventions. Lewis cites one study which showed that even when people can maintain sustained attention, the very presence of mobile phones reduces “cognitive capacity,” leaving little room to carry out other tasks.

For some great experimental prose, this oldie but goldie by Eugene Lim, titled Portrait of a Cyborg, captures the mental gymnastics that come with this deficit in attention.

“Wake up, look at phone. Any likes?”

Feeling creative

This period helped me reconnect with my interest in design, prompting a rebranding experiment on Cultural Learnings.

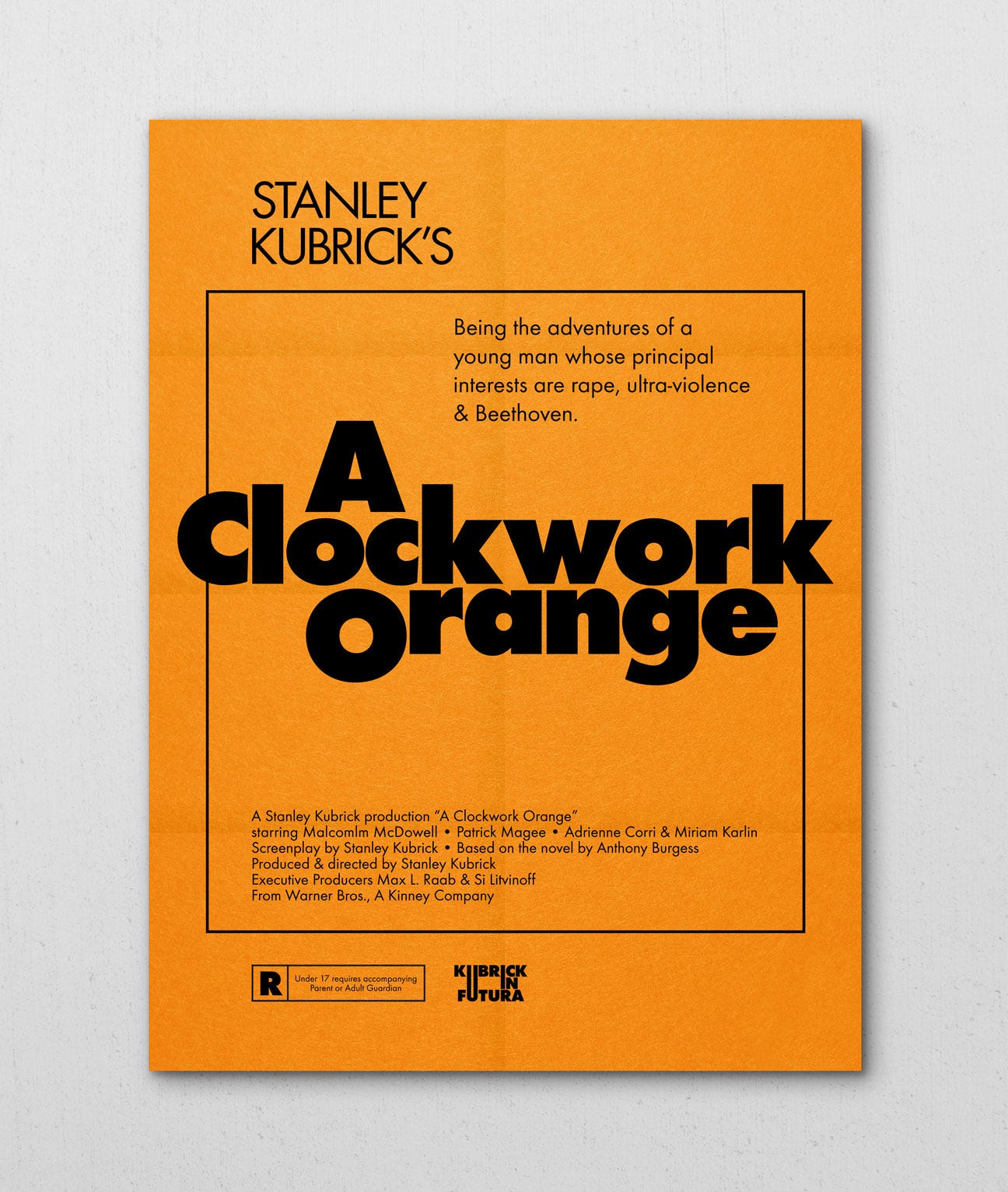

Futura Condensed Bold was my inspiration – the font used for the logotype at the top of this newsletter. Designed by Paul Renner in 1927, the Futura typeface captured the spirit of Bauhaus by combining “beauty with function,” unifying “principles of mass production with individual artistic vision.” (Uniqlo?)

From Wes Anderson to Nike’s “Just Do It”, Futura has elegantly conveyed some of history’s most powerful messages. Eye on Design provides a comprehensive summary of the “modernist typeface that is literally everywhere.”

This omnipresence is the reason why Douglas Thomas, in his book Never Use Futura, protests against using the font, calling it “the Great Satan of clichés and the Little Satan of naked convenience.”

Futura was used to advertise two of my favourite films, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969) and Irreversible (2002). So, to me, using Futura is like paying homage to the films that inspire me.

Plus, it’s beautiful. Who are you to say what I should and shouldn’t like?

This iconic opening sequence from Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void (2009), much of which uses Futura, is probably my favourite exercise in typography ever. Please don’t watch it if you’re epileptic. You can also read an interview with the designer, Tom Kan.

Good

The most common response to the question of how I am doing is a short one: “Good.”

Yet, it is also the vaguest answer anyone can give. You’re “feeling” good? You “are” good? Good at “what”? I’m convinced most of us (including me) do not really know what it means to say “I’m good.”

Well, wonder no further. Simran Sethi from The New York Times does the heavy lifting as she talks to monks, CEOs and therapists on the essence of goodness and how to practice it. “Goodness is an act of being and doing,” she defined, “requiring that we not only engage but reflect on the intentions behind our actions.” One of the most interesting responses came from Dan Ariely, a behavioural economist from Duke University, who had this to say about putting challenges in perspective:

if you save one person, you can look at yourself as somebody who has saved the whole world. In that regard, what goodness means is to scale the problem down to the size where we can have an impact — and then have the impact.

Reflecting on our actions requires deriving meaning from them – even the painful ones. John J. Donahue, a psychotherapist and behavioural scientist from the University of Baltimore, discusses on Aeon how adjusting our response to suffering can help overcome challenging situations. It is not about reducing problematic thoughts, but fostering meaningful “behaviours regardless of mood, motivation or thinking … Think of [it] as going about your daily life in the service of values that you find important, whereby engaging in these actions creates a sense of meaning and purpose.”

Other definitions of good are these bois right here:

Miscellaneous items

Want to find out if the person next to you in the grocery store has coronavirus? There might be an app for that soon, as explored in The Intelligence on Economist Radio.

In this supercut, artist Benjamin Grosser spliced Mark Zuckerberg’s every recorded appearance between 2004 and 2018, creating a hallucinating mantra chanting “grow,” “more” or utterances of numbers. Grosser also created a Firefox extension to hide your notification metrics on Instagram.

Game developer Nicky Case uses game theory to illustrate our “epidemic of distrust” with this interactive explainer.

This podcast episode of Is This Working asks: “Is anyone actually getting work done?”

On the importance of typography in the film Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017).

A hand-washing guided meditation for the coronavirus era. Guaranteed to clean your hands and brain.

Cultural Learnings is a newsletter written by Sai Villafuerte. You can support it by subscribing, sharing this post, emailing your thoughts or answering this survey.