Where's the dancefloor?

Music producer and DJ Javier Pimentel on disco, queer spaces, and finding inspiration.

Cultural Learnings is an editorial platform for discussions on contemporary culture, curated by Sai Villafuerte. You can support it by subscribing to this newsletter, sharing it with your friends, emailing your thoughts, or answering this survey. Cultural Learnings is on Manila Community Radio every Wednesday, 17:00 - 18:00 GMT+8. You can access the radio archive here.

One of the last mass gatherings I attended: Floating Points at Printworks, London, November 2019.

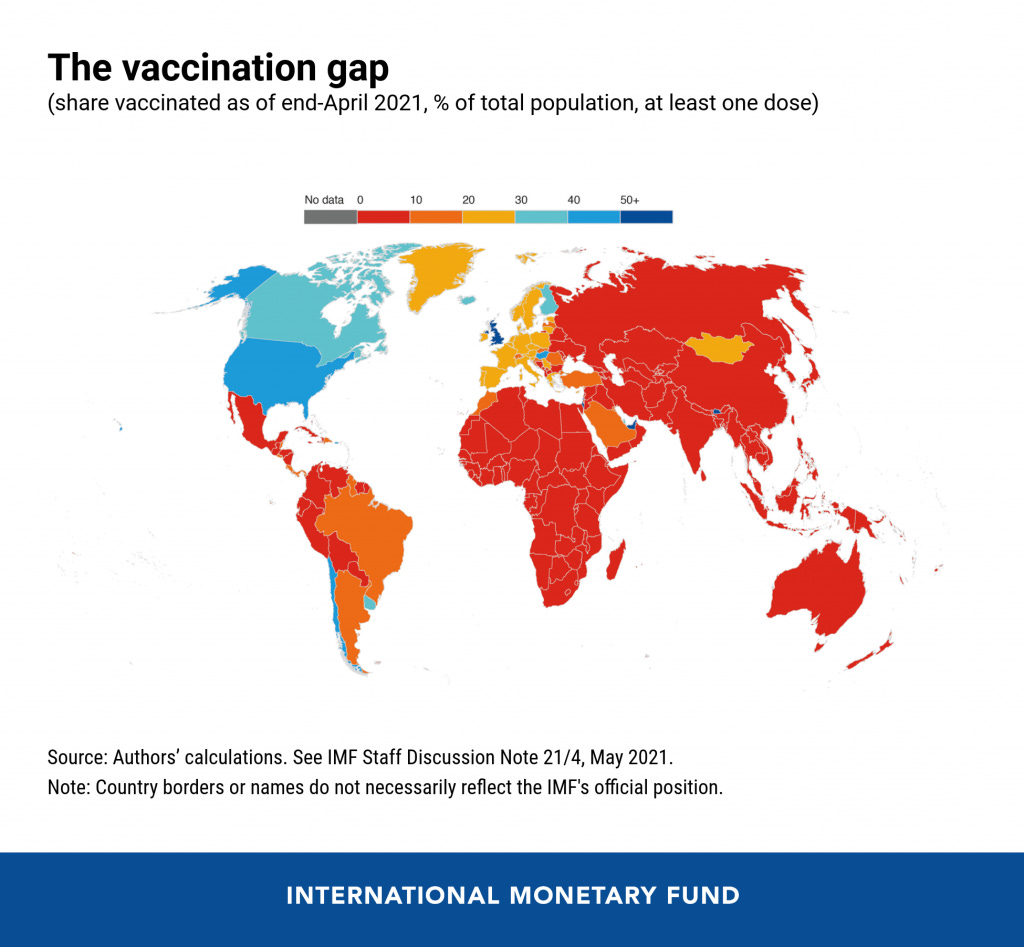

It’s been crazy to see the rest of the world, namely the Western hemisphere, re-entering into public life with social gatherings left and right. Despite life in London still relatively fresh in my mind (I used to live in England for seven years), I struggle to imagine swathes of people there convening in public spaces while much of the world is still grappling with how to handle a pandemic.

The UK government’s Events Research Programme launched an initiative to examine the risk of transmission from attendance of events with ten to fifteen pilot events. The initial results found that attending one without face masks and social distancing is just as risky or “Covid-safe” as going to a restaurant or a mall (subject to tests and other rigorous on-site safety measures, of course). In fact, just 15 out of 58,000 attendees of the UK trial events tested positive for Covid. That’s an astonishing number.

Meanwhile, the Philippines is one of the very few countries in the world where wearing a face shield is required indoors and outdoors, despite the lack of scientific evidence proving its efficacy. Many cultural establishments in Manila have permanently shut their doors, leaving very little to return to once everything is “back to normal,” if ever it does.

This is something my friends with retail spaces, restaurants, and event companies are struggling to communicate – namely, how people choose to spend their money “doesn’t only satisfy an immediate craving, but it acts as an investment in a promise that social spaces will continue to exist when this is all over.” It feels a little unfair that some feel at liberty to celebrate the “light at the end of the tunnel” while suffering for the majority persists. I’m not entirely sure what the end of the pandemic will look like on my side of the world, but I’d like to think we’re all doing our best to keep the party spirit alive – whether that’s supporting local cultural establishments or finding safer ways to congregate together.

For this third edition of Cultural Learnings’ Pride Month programme, we invite Javier Pimentel, also known by his monikers Papa Jawnz and lui. (pronounced “lui with a dot”). Tomorrow (Wednesday) on Manila Community Radio, he will deliver his re-imagining of a Studio 54 party – a legendary disco nightclub in New York City, attended by the likes of Grace Jones and Andy Warhol, known for being one of the first mainstream queer-friendly clubs in the world.

Below is my interview with Javier, where we talk about disco, queer spaces, and how he finds inspiration. Enjoy!

How are you, Javier? What have you been up to?

Since quarantine, I’ve been keeping myself busy. The biggest life update is that I just started my internship with a music solutions agency. I like that they work agnostically by contributing to the whole music industry, whether it’s getting the underground scene more recognized or curating the mainstream. That’s really hard to do, but it’s also really noble. That diversity reflects in the people that work there too. It’s only been a week, but I’m excited to guide myself in the company and contribute where I can.

I want to talk about your musical background. Could you describe your sound as Papa Jawnz versus lui.?

I guess my sound is just bits and pieces of stuff from the past. lui., which is my main project and where I produce original music, started out with sampling hip-hop and lo-fi, which I really like doing because it recontextualises something from the past that people maybe didn’t appreciate then. When I DJ as Papa Jawnz, I like to play obscure stuff people have forgotten – a lot of disco and world music, especially Filipino music I didn’t grow up with but wanted to learn more about.

I was very careful with the way I framed that question. I asked, "Could you describe your sound?" instead of asking what genre of music you play. What you answered was not about the sound per se but the concept or method you go about looking for that sound, like “things from the past” or sampling old music. As an artist, are you aware of this way of viewing your music?

I’m just inspired by what I'm listening to at a given time. I try not to make music in the “formatted” style of a genre. Like every artist, I’m finding my space within a specific genre. I always have a reference in mind, and I try to add something that’s uniquely mine.

What is your process for finding inspiration?

I normally start research by digging for music. Sometimes, I stumble upon tips for music production online, so I try it out. I also like catching up with my fellow producers and artists to exchange ideas and see what they’ve been doing; it reassures me that I'm not the only person having a creative block.

I also think inspiration comes and goes. A friend once told me that as much as creativity is a feeling or a wave, it's really a muscle you have to keep building. Luis Montales also told me something similar when I asked him what he does when he’s uninspired to make music. He said: “Just make a 16-bar loop then leave it at that. Eventually, you’ll look back and see where it goes.” Or maybe that’s it.

I’m interested in how you view disco, which is the genre I largely attribute you to. What draws you to disco?

Disco is so emotional. I got drawn into it after going to the club more, watching my friends spin disco. It can go from the start of crying to feeling uplifted and happy. It’s also so fun to dance to. Before I started clubbing, I wasn’t listening to much disco but seeing how receptive it is in the context of a dancefloor, I realised how much I liked it.

It might also have something to do with me being Filipino. Filipinos love singing at parties, and disco is ten minutes of singing along at a party. [Laughs]

Studio 54 is a queer space that gets thrown around a lot in popular culture. What do you know about it?

My first exposure to Studio 54 was from my parents. It was the “cool” club and, to them, the music that came out of it was “disco.” I watched some hip-hop documentaries that mentioned Studio 54 which, apparently, invited the early hip-hop, New York Harlem DJs for what was their equivalent of an “alternative” club night. So, Studio 54 was at an intersection between hip-hop and disco for some people.

But one of the things I noticed [about Studio 54] was that it’s really white. A lot of black people were denied entry into the club, despite disco being African-American. Maybe the lack of it being seen as an African-American space is a little problematic.

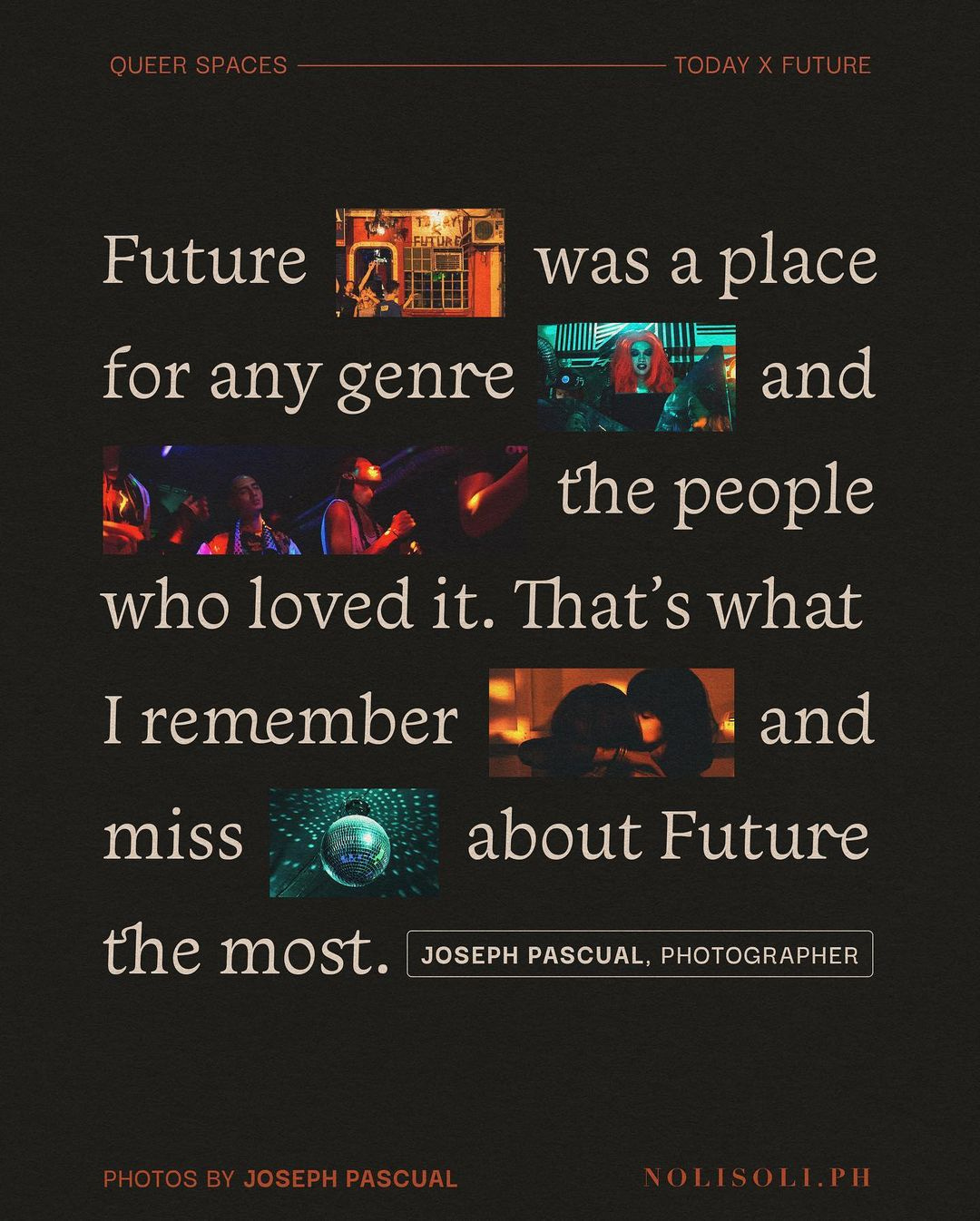

I think this conversation is really timely. Exactly a year ago, Today x Future closed down, which was a really popular queer space in Manila. I’ve never been because I was living in London. But what was it like having that type of space?

In the Philippines, you have your bottle-service luxury super clubs. Then you have places like XX XX, which are in the opposite side of that spectrum with parties like Elephant playing underground techno music. TxF was a great middle ground. You can have a “Twitter thirst trap” playing all the queer bangers on Virtual DJ then, next thing you know, someone is playing hard techno.

When I was around eighteen, TxF already had that reputation as one of those legendary venues. To me, it was, first and foremost, an underground music space. They had a lot of underground acts and they gave a lot of people their first gigs. After going there more often in college, I realized it was a queer space, which made it less intimidating. It was an experimental and extremely open-minded club that wasn’t in the most expensive areas of the city. Everyone is really sad it’s gone.

Source: nolisoli.ph

How has the queer community shaped your taste in music?

I really like it when people are receptive to the music I play and I usually get that from queer people. They’re just game to dance and have a good time. Not that they don't care what's playing but, in my experience, they won't complain and tell you to leave. They’ll often try to understand and find a way to enjoy it. As a DJ, I’ve experienced the humiliation of having the crowd talk shit about the music I’m playing. I’ve also played in gigs where grown straight men made fun of my friends for dancing in a club. It’s like, dude, why are you laughing at my friends for dancing? Why are you here?

If you don’t mind me asking, what do you identify as and how did you come to that realisation?

I normally tell people I’m bi. But it’s more of: if I like someone, I like someone. One time, I acted on that and it didn’t feel weird, so that’s when I knew. Of course, that’s the small gist of the trauma queer people go through. In the Philippines, people bully you for being femme. That’s so sad. I’ll always make an effort to stand up for people being pressured for who they are.

I noticed queer people are always hesitant in putting a label on their identity. “I think I’m this, but I’d rather not call it this.” Why do you think that is?

Personally, I’m still figuring out who I am. By putting a label on myself, it might prevent me from discovering other things.

What do you think is the most misunderstood thing about the queer community?

There’s an expectation that queer people have to fit into a stereotype. Like, I’m queer but I still watch football and play video games. When someone comes out, it’s not like they do a complete 180-degree lifestyle change. You don’t have to like what the stereotype of a culture is meant to be.

Also, the “A” in “LGBTQA” stands for “asexual,” not ally!

You can follow Javier on Instagram, Twitter, Bandcamp, and Spotify.

Javier’s three Cultural Learnings:

Play Apex Legends (“It’s free and cross platform!”)

Listen to Hunee, his favourite DJ.

“Get your friends, make a group chat, and share shit that they’d buy from Depop and Facebook Marketplace.” (“Dude, this is not my size. Go for it, and I'll live vicariously through you.”)

We’ve covered disco on Cultural Learnings before. You can read and listen more about it here.

I watched the show Halston on Netflix recently and I highly recommend it. It’s about the rise and fall of the fashion designer Roy Halston Frowick, who was a frequent visitor of Studio 54.

Chemsex is a really interesting and educational documentary from VICE on the use of drugs like GHB and mephedrone in London’s gay nightlife scene.

Matthew Schneier described the “fear of missing out” as “the performance of plans” in this piece on The Cut about how FOMO is back in New York City. “Now my phone glows with scheduling and agita … All over a jittery city, the excitement of reentry is colliding with the anxiety of abundance.”