A photograph I took of Capitol Theatre in Escolta St., Manila, under the rubble — once the home of MGM Pictures in the Philippines during the post-war era. I wrote about the struggles of preserving cultural landmarks for CNN Life. You can read the article here.

A few weeks ago, I contemplated on my recent hiatus from Cultural Learnings; how I was grappling with my online fatigue by making sore attempts at slowing down my creative output. I actually wrote my first newsletter ever, “Can we have slow media?”, in April 2019 after deciding to leave Facebook. While short-lived, leaving Facebook stemmed from wanting to create slower and more intentional ways of keeping in touch with friends — a response to, what I called then as, “recent upheavals concerning data privacy, millennial burnout, and time-wasting.”

Realising I struggled with these same issues nearly two years later, that there was no Quick and Easy™ solution to our fibre optic existence, was slightly worrisome. Yet, it was reassuring to find that “red thread” in my writing — a term originating from the German expression “der rote Faden des Erzählens” or the “common thread” in a story. When you commit to something, you hope to find, over time, consistency in the thing you spend years slaving away on. So, it was reassuring to know that I have, to use another idiom, come “full circle.”

After I published “How is your 2021 so far?”, I received an e-mail from a reader with his own soliloquies on slowing down. Slowness, he implied, requires the focused attention of its subjects — a necessary ingredient for cultures to thrive. Yet, slowness is becoming an increasingly unobtainable ideal. That is not to say slowing down is impossible, but it sure feels like it when everything is aggressively condensed for convenience — a “monoculture” appearing most clearly, he suggests, in everyday language.

For example, I’m reminded of a phenomenon called “character amnesia” or 提笔忘字, literally meaning “to pick up the pen and forget how to write the character.” Common among young people in China, Taiwan, and Japan, this phenomenon is largely attributed to overreliance on modern keyboards where people can enter a character without writing it by hand. Last year, in the Philippines, there was a backlash against a sign in an underpass using a pre-colonial script called Baybayin. The sign mistranslated locations by omitting the dots used on top of some characters — perhaps the result of translating from English instead of Tagalog. Baybayin is also not taught in schools or used by the general population, making it a functionally extinct script. These examples illustrate how a global Anglicised culture is perpetuated by technology, standardising language to fit the convenience of the English speaker.

“I have heard a Russian couple struggling to speak English with an Italian waiter in Venice and a Danish couple ordering in fluent English from an Icelandic waiter in Reykjavik. We could have been in New York.”

— Alan M. Stevens in response to Pamela Druckerman’s article, “Parlez-Vous Anglais? Yes, Of Course.”

In fact, there may be a relationship between language extinction and biodiversity loss, creating monocultures on biological fronts too. The loss of biodiversity, according to the United Nations Environmental Programme, was disrupting local ways of life, leading to the homogenisation of cultures. “Cultural change, such as loss of cultural and spiritual values, languages, and traditional knowledge and practices, is a driver that can cause increasing pressures on biodiversity … In turn, these pressures impact human well-being.” In fact, the rapid spread of English all around the world easily exceeds the rate of global language loss, leading experts to believe that fifty to ninety per cent of the world’s 6,800 languages are expected to disappear before the end of the century. Perhaps it is no coincidence that since the 1970s, the decade globalisation entered a new frontier, nearly 1/3 of all the wild species on Earth became extinct.

Of course, to say we live in a strict monoculture would betray the many cultures existing outside the English-speaking world. I only want to illustrate how our difficulty to practice slowness may be partly due to the belligerent, technological processes behind our pandemic of sameness.

Below is the e-mail I received from Marc, the reader who wrote to me in response to my previous newsletter. I hope you find some food for thought as I did.

“Have you ever read The Lord of the Rings?”

The Laguna Copperplate inscription, containing early forms of Baybayin, is the earliest calendar-dated document used in the Philippines, written in Shaka year 822 (Georgian A.D. 900). Before the Copperplate was discovered, Filipino history was less than 500 years old.

“When I think about "slow culture," I think about the bit in “The Two Towers” where Merry and Pippin are discussing Ent culture with Treebeard. There is a word in Entish that means "hill" and it's fifteen syllables long. Don't ask me to write it, I can't remember it. [Editor’s note: That word is “a-lalla-lalla-rumba-kamanda-lindor-burúme”.] The hobbits think everything the Ents do takes too long; the ents consider the hobbits rash and impulsive. The Entmoot famously takes an entire day just for each ent to introduce itself and greet the rest.

When I read this chapter, it made me think about Gàidhlig culture and my old teacher had an uncle whose name was (or so she claimed) Domhnall Domhnall Domhnall Domhnall Domhnall Domhnall Domhnall mac Domhnall. His name was Domhnall, as were the names of all of his fathers before him. It seems unthinkable to name a child something like this now. In fact, when I changed my name legally to Marc Ruadh … … …, Facebook later told me it was too long. [Editor’s note: Each ellipsis indicates a part of Marc’s name he requested to keep anonymous.]

It seems to me it is not only social media and journalism that have changed to become more easily consumable. Entire cultures, especially English language cultures, have slowly shifted towards a preference for ideas that don't outstay their welcome. If English is the language of capitalism, then it’s only natural to suggest that as capitalistic technological pursuits sped up industrial processes, so too would names shorten to accommodate this.

Not only that, but Hollywood would take great strides to make sure their stars had short and catchy names — like Kirk Douglas or James Dean. No doubt audiences clamoured to affect that kind of star power when they named their own children. When I chose my stage name, I too wanted a short, catchy name and chose Mark Douglas, even though Douglas has nothing to do with me or my heritage — culturally speaking — besides the fact that it is also a Scottish name. I remember rejecting the idea that Paterson, my birth surname, was Scottish at all and didn't want to use it as a stage name. The truth is more like I cared less about my own heritage than I did about becoming a famous actor with a catchy name.

I think there is still a cultural pull in the film world for well-known directors like Apichatpong Weerasethakul, only to give themselves daft nicknames like "Joe” — presumably so that white Westerners don't have to go through the awful hardship of learning two words.

Anyway, this leads me on to a question I've wanted to ask for a while and now seems like an appropriate time to ask: is Sai short for something?

Dùrachdan,

Marc Ruadh … … … … … … … … …”

Dig deep

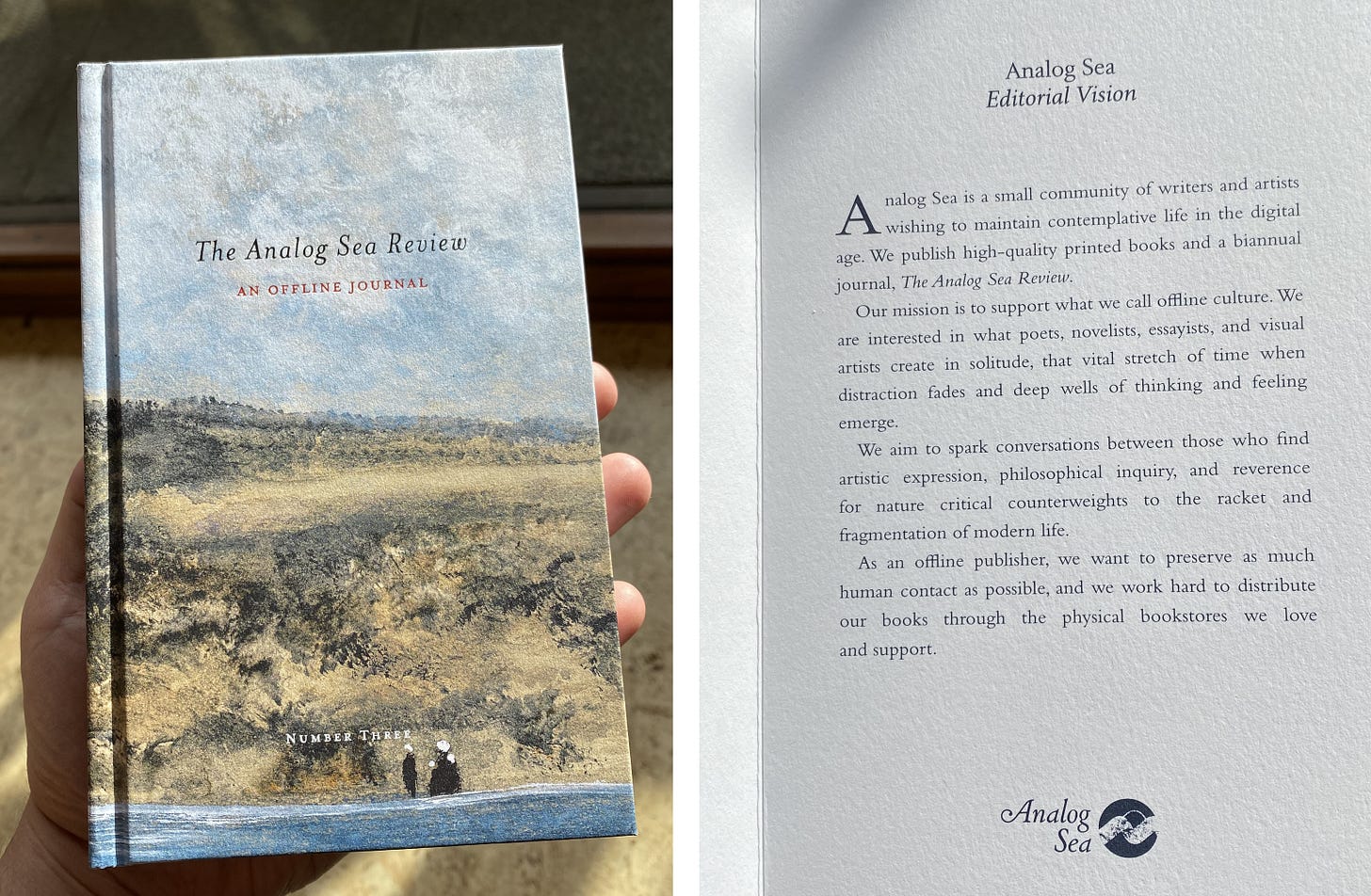

A copy of The Analog Sea Review, a literary journal published between offices in Texas in the US and Freiburg, Germany. Analog Sea is an “offline publisher” so if you want to purchase this beautiful piece of print, you have to visit their physical stockists or send them a letter — no e-mails! This photo was shared by my friend, Danny.

If you fancy some hip-hop and R&B, I recently made a guest mix for Refuge Worldwide — a Berlin-based community radio. I also created a Daft Punk retrospective for my weekly show on Manila Community Radio, mostly featuring tracks by Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo before they formed the duo.

This long-read from Vox looks at whether monocultures can survive the algorithm.

George Orwell’s five rules of writing from his essay, English and the Politics of Language:

1. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

The world’s longest town name is in New Zealand and has 85 letters: Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu. A close second is the Welsh town of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. You can find the pronunciation of these words in the respective videos below.

Cultural Learnings is an editorial platform curated by Sai Villafuerte. You can support it by subscribing to this newsletter, sharing it with your friends, emailing your thoughts, or answering this survey.

Cultural Learnings is on Manila Community Radio every Wednesday, 5-6 PM GMT+8.